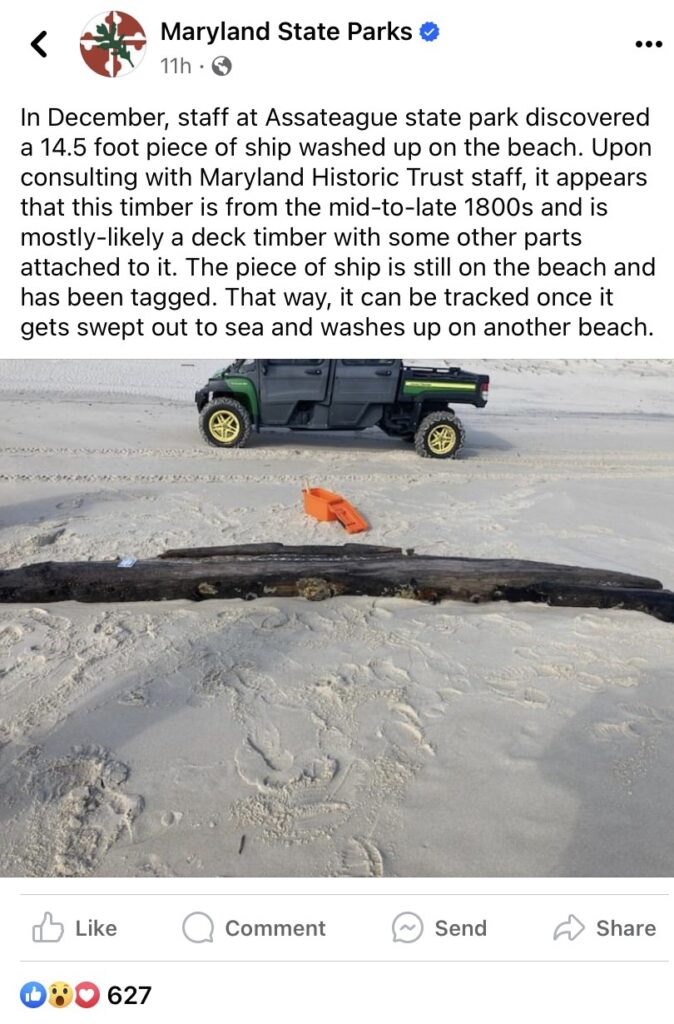

It was an eye-catching bit of news from Maryland State Parks on Facebook: in December, staff at Assateague State Park discovered a 14.5-foot-long piece of ship washed up on the beach. It’s believed to be from the mid-to-late 1800s.

It sounded like a discovery that should end up in a museum—right? But the state simply tagged the deck timber and left it on the beach to be swept out to sea again, perhaps to wash up on another beach.

Facebook followers who saw the post expressed confusion. Why wouldn’t authorities bring the timber to a lab to study it? Why wouldn’t it go on display in a museum? And why would a nearly 15-foot-long piece of wood be allowed to float back out as a potential hazard to navigation?

and some confusion.

There are a few reasons the timber is being left to nature, state underwater archeologist Dr. Susan Langley tells Chesapeake Bay Magazine.

Because of some distinguishing features, Langley says she can estimate a rough date for the ship piece (mid-to-late 1800s) and can tell what part of the vessel the timber is from. It’s a floor timber from the bottom of the ship, just above the keel, she tells us, explaining that she can see the spot where the timber was attached to a futtock (the next section of the frame/rib). And the squared-off, multi-sided treenails (also known as trunnels) found in the timber weren’t typically used past the 1800s. Technically, she says, the timber could even be from the 1700s.

Langley says because floor timbers are breaking off this mystery shipwreck, the indication is that the entire ship is breaking up—right down to the bottom.

Beyond that, however, there aren’t enough clues to make it a historically significant artifact to, say, preserve it and put in a museum. That costs thousands of dollars. Because most timber was imported in shipbuilding back then, even the type of wood used doesn’t tell us which part of the world the ship hailed from.

Langley says the timber’s greater value is in tagging it and waiting to see if it ends up on another beach along the coast. Rediscovering it later can offer insight about ship worms and other wood-boring creatures that target shipwrecks and about climate change.

But wouldn’t a timber this large be a marine hazard floating at sea? Unlike the logs we find in the Chesapeake Bay that pose navigational hazards, this piece of wood is so heavy and dense that if it’s swept out, it would likely sink to the bottom. “It won’t come up; it would take a very bad storm to bring it to the surface, when no one is out,” Langley says.

She also dispels a notion that some Marylanders wondered about: because it washed in from the ocean, is it considered foreign property? Actually, Maryland State Parks says, any artifact found within the waters of Maryland belongs to the state. If the piece had identifying elements showing exactly which vessel or foreign country it came from, laws would come into play related to military or maritime vessels. Based on the limited information available about this timber, that’s not the case.

Angela Baldwin, park manager at Assateague State Park, says even if the wood wasn’t significant enough for a museum, this was a notable discovery.

“We have had many shipwreck pieces wash up after strong storms over the years, particularly during the winter months, however, this one is a little larger than what we have seen in the past—and thus has drawn a bit more attention—but they are always exciting to find!”

It will likely take awhile for the piece of ship to wash back out to sea, so curious observers can walk out on the beach to see it for themselves. Baldwin says, “It is an easy walk from our day use area towards Loop B of the campground where you can see it in person.”

Any beach explorers at Assateague State Park can participate in the citizen science program, Baldwin tells us. And Langley says, “Don’t be afraid to go touch it. You can’t really hurt it. Go play with your history!” Langley notes the ship timber could be a great project for a class to go and examine, while it’s still there.

All visitors can check out kits so that if they come across an artifact, they can collect and submit the data as part of the STAMP program. This multi-state program coordinated in Florida engages the public in documenting and monitoring shipwreck sites and tracking the movement of shipwreck timbers along the coast using QR-code tags.

STAMP data from this latest shipwreck can be seen here.

The STAMP program was inspired by a Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge-U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service project. A timber tagged at Chincoteague in September 2014 only moved 40 meters in a year’s time. Then in 2015, several harsh winter storms hit the wildlife refuge and by January 2016, the timber had traveled at least 106 miles to Corolla, North Carolina on the Outer Banks.

Dr. Langley has plans to train more citizen scientists in the future to help track shipwreck debris.