Humpback whales are dying in the lower Chesapeake. Researchers are working to find out why.

By Wendy Mitman Clarke

Mid-morning at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, and the apparent wind whipping through the 26-foot RIB skimming across the surface is anything but balmy. It’s January, and the people on board are kitted up like skiers with goggles, balaclavas, gloves and multiple layers of fleece and foul-weather gear.

Barely half a mile out from the bridge at Lynnhaven Inlet, they spot what they’re seeking, as mist spouts into the crisp blue sky. Beneath, the glistening grey massifs of the whales’ backs—the eponymous humpback—part the water with barely a ripple.

The RIB, from the Virginia Beach firm HDR, approaches slowly and the researchers on board begin their work, noting the position, the time, and what the whales are doing. They photograph each whale and compare backs and tails to enlarged images in a binder—a visual catalogue that can help them identify whether this is a new individual or one the team has identified and tagged before.

If it’s a new whale, the team carefully maneuvers the RIB alongside and shoots a small titanium dart with a satellite tag attached through the cartilage at the dorsal fin, and for the next several weeks, until the tag falls off, they will track the whale’s movements.

They back away, finish making their notes, and simply watch as the whales, majestic as silence, part the cold, clear water of the morning, their exhalations heavy in the still air.

Hopefully, this will be the last they see of these whales, until another tagging trip this year, or maybe sometime next winter. But lately, that’s not been the case.

More and more often, young humpback whales who are feeding in the waters near and in the lower Chesapeake during the winter and early spring are washing ashore along its beaches, many of them the victims of ship strikes. February of 2017 was a particularly grim period, as three humpbacks washed ashore within 10 days, one with the open slashes of propeller wounds on its head and body, the other two with similar injuries.

In the Chesapeake, the whales are running the gauntlet of Hampton Roads, home of the sixth-busiest container shipping port in the U.S. and the world’s largest Navy base at Naval Station Norfolk. But the increase in humpback whale deaths on the entire East Coast has prompted the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Fisheries Service to declare an unusual mortality event, or UME, from Maine to Florida. In the past three years, ship strikes have killed humpbacks along the East Coast over six times more than the 16-year average, NOAA says.

“That’s a pretty staggering number,” says Alexander Costidis, the Stranding Response Coordinator for the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center and one of a very few people in the country with the experience and permission to conduct whale necropsies.

The UME, declared when a species is suddenly dying more than expected, is essentially an all-hands-on-deck for scientists to get a better handle on what’s happening. The investigative workgroup developed as a result of the UME includes the Virginia Aquarium, where Susan Barco, Research Coordinator and Senior Scientist, and her colleague Mark Swingle, Director of Research and Conservation, have been studying whales in and near the Chesapeake for 30 years.

“Mark and I both grew up here, and neither one of us remember ever hearing about whales in the area,” Barco says. “The Bay has recovered a little bit, and humpbacks have been recovering, so our thought is that it’s probably either an increase in population or a shift in the prey base, or a combination of those and other factors.”

But Barco says that scientifically, so far, there’s no smoking gun other than what is circumstantially obvious: “We have a lot of ships in this area and have had for a long time. I can’t back it up scientifically, but circumstantially it certainly makes sense if there are more whales and more ships there will be more interactions. And whenever a ship and a whale interact, it’s not good for the whale.”

Humpback whales are found throughout the world’s oceans, with 14 distinct populations. They can live up to 80 or 90 years, reaching sexual maturity between four and 10 years, and females produce one calf every two to three years.

Some populations are still endangered or threatened, while others have rebounded significantly since 1985, when commercial whale hunting was banned. Before that moratorium, humpbacks were hunted to near extinction, with some populations cut by 95 percent. NOAA Fisheries estimates based on a survey from the mid 1990s indicate that 10,400 to 10,752 humpbacks now live in the North Atlantic.

All humpbacks are protected under the Marine Mammal Protection Act, but the whales that we see in the Chesapeake, which are part of what’s called the West Indies population, are no longer considered at risk. They breed and give birth in late winter and early spring on the Silver Banks, a broad area north of the Dominican Republic. In summer, they migrate north primarily to the Gulf of Maine, although some have been identified from whales who feed in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and off Newfoundland, Barco says.

Most of the whales that are turning up dead in the Chesapeake are juveniles, who evidently are spending more time here as youngsters after weaning from their mothers.

“We could be seeing some animals that are as young as a year old,” Barco says. “Most are a little older. We think they are mostly eating schooling fish, which can be bay anchovies, croaker, menhaden. We think menhaden is one of the primary prey, but in stranded animals we’ve seen some of those other species in their GI tract.”

Since the early 1990s, Barco and her colleagues at the Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center have been conducting the longest survey of whales off Virginia and the mid-Atlantic, developing and curating the Mid-Atlantic Humpback Whale Catalog, a regional catalog of high-quality humpback identification images and sighting data.

“We started getting sightings of whales very close to shore in the early 1990s and started documenting them mostly from shore from 1990 to 1992,” Barco says. “That also coincided with us getting strandings in the area. My first stranding was in 1990, and I think we had two to three that year. So, the sightings and strandings started at the same time.”

A paper published in 2002 in the Journal of Cetacean Research and Management, of which Barco was lead author, notes that between 1990 and 2000, there were 52 reported humpback whale deaths in the mid-Atlantic states (New Jersey through North Carolina). Of these, 13 were in Virginia, 81.2 percent of them were first-year whales, 14.6 immature, and only 4.2 percent were mature whales.

“Of these, the cause of death could not be determined for 39 (75%),” the paper says. “For the remaining 13, 11 were identified as being due to entanglements in fishing gear or collisions with vessels, whereas two showed no signs of human-induced mortality.”

While Barco’s research found 52 humpback deaths over 10 years in the mid-Atlantic states, NOAA Fisheries has since documented 39 deaths in the same states over just the past three years. In the Chesapeake, 13 whales were killed in Virginia in the ten years between 1990 and 2000, while 14 were reported in the three winter field seasons between 2016 through 2018.

The NOAA Fisheries UME for humpbacks began on Jan. 15, 2016, when a dead humpback whale was reported off Virginia Beach. (There are also current UMEs for minke and right whales on the East Coast, although the majority of these whales are dying in New England).

Since January 2016, NOAA Fisheries has documented 84 dead humpbacks in the UME as of Sept. 30, 2018. The highest numbers of deaths were off New York, with 17, and Massachusetts and Virginia, which tallied 14 each. Of the latter two, the majority of whales died in 2017, with each state reporting seven deaths in that year.

Many of the stranded carcasses couldn’t be retrieved for examination, but partial or full necropsies were performed in 2016 and 2017 on 20 of the dead whales, and of those, half showed evidence of collisions with a vessel, far more than expected.

“Of the 20 cases examined through April [2017], 10 cases had evidence of blunt force trauma or pre-mortem propeller wounds indicative of vessel strike, which is over six times more than the 16-year average of 1.5 whales showing signs of vessel strike in this region,” states the NOAA Fisheries FAQ.

Complementing the work of the Virginia Aquarium is the US Navy, whose Mid-Atlantic Humpback Whale Monitoring project, led by HDR, is further identifying individual humpbacks and using satellite tagging to better understand their movements.

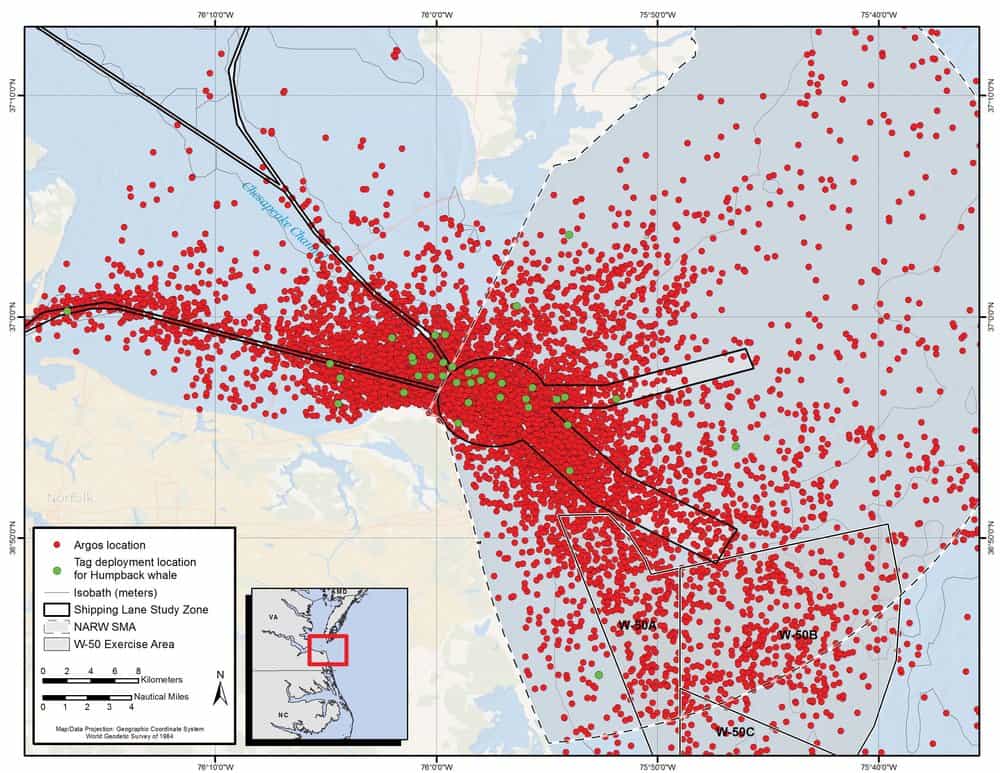

Begun in January 2015, the study, as of October 2018, had compiled a catalog of 119 individual humpback whales. In December 2015, HDR’s scientists began using small satellite transmitters to track the whales for several weeks and map their movements in and near the shipping channels and several Navy training areas just offshore. What they’re finding is that the whales spend a great deal of time in the deeper waters of the shipping channels, presumably feeding on the prey drawn there.

“A high percentage of our animals that have been satellite-tagged are spending a considerable amount of time in shipping lanes, about 50 percent of their time for some individuals and even higher for some others,” HDR project manager Jessica Aschettino says. “We’ve seen more than half of our tagged animals move on the west side of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, which I think has been a surprising find for us all.”

According to an August 2017 project report, 57.7 percent of tagged animals during the 2016/17 field season were tracked west of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. “This was a large increase when compared to the 2015/2016 field season where only 22.2 percent had locations west of the CBBT.”

The 2017/18 season was a bit of an anomaly, with the whales spending more time offshore and fewer coming into the Bay. Scientists believe this was due to the colder water temperatures of last winter driving the whales’ prey further offshore, taking the whales with them.

“When zooming in on the primary study area at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay using tag data collected from all field seasons, the importance of this area to humpbacks whales (and fin whales) is apparent,” HDR’s 2018 report says. “Nearly a quarter (2,570 of 10,517) of all filtered tag locations were inside shipping channels, and approximately eight percent (808/10,517) of locations were inside the W-50 MINEX zone [a Navy training area just offshore of the Capes].”

During the 2016/17 field season, of 172 total large whale sightings, “87 (50.6 percent) occurred in the shipping lanes (all humpback whales).” Similar to Barco’s findings, the majority are young—76.3 percent of those in the 2016/17 field season were categorized as juveniles.

“Interactions with vessels, both large and small, are a significant cause for concern for both humpback and endangered fin whales in the study area,” HDR’s report says. “During the 2015/16 season, three individual humpback whales were observed with boat injuries … ranging from non-life threatening to likely fatal injuries. During the 2016/2017 field season, three humpback whales were killed in a 10-day period, all with evidence of vessel interactions that likely led to their deaths. A fourth whale was observed with severe injuries from a propeller. The 2017/2018 field season also started off with the death of a known humpback whale.”

So, what can be done? According to NOAA Fisheries, speed restrictions imposed on ships to protect right whales, including those off of the Chesapeake, can benefit other whales. From November through April, vessels over 65 feet must travel 10 knots or less in these areas. But the zone at the Chesapeake starts at the line between the Capes and then arcs offshore, so that the shipping channels inside the Bay aren’t restricted.

If that zone could be extended further into the Bay, Aschettino says, it would benefit the whales.

“We have seen ships that are abiding by that speed restriction through the Bridge-Tunnel, and then as soon as they’re through there they pick up speed. And we know whales are feeding there,” she says. “It’s been shown in other areas that oftentimes the shipping companies are willing to cooperate, but it is a big ask for them to slow down. Time is money, and all of that. So, we’re hoping to put together this full data set and have some good motivation for them to participate and help out. But ultimately it’s going to be the regulators who would want to change and enforce it.”

Not only is slowing down anathema to tightly scheduled shipping operations, requiring ships to slow down too much in constricted areas like around the Bridge-Tunnel can be dangerous.

“Large vessels need to maintain some speed to steer, and when you put them in narrow waters where there are bridges and tunnels and you try to slow them down, there are problems,” Costidis says. The geography of the Bay’s shipping channels is also problematic, since they are relatively narrow, funneling the ships, the fish the whales want to eat, and the whales into the same space.

“Our channels are not particularly deep, and in some cases with these larger ships that are quite full, there may be very little distance between the bottom of the ship and the channel, so there’s no deepwater refuge for these animals at all,” Barco says. Also, while it may seem that a whale should hear a ship bearing down on it, the quietest area of a ship is right in front of it, and whales that are feeding are highly preoccupied already.

“When they’re feeding and having sex you can pretty much do anything to them and they don’t respond,” Barco says. “Normally when they’re swimming they would see vessel noise as a threat, but when they are feeding they probably don’t.”

This season, HDR’s scientists are continuing their work identifying and tagging humpbacks in the Bay and just offshore, adding a new collaboration with Duke University. Duke scientists will be using a different tag which can provide data about whales’ movements underwater, how deep they are going, and even acoustic information, Aschettino says. For instance, if a whale is submerged and a ship is approaching, the tags should be able to identify the sounds of the whale and the ship and determine whether and how the whale reacts by changing position or orientation.

Though these whales are not considered endangered, Aschettino believes that as people become more educated about the humpbacks in and near the Chesapeake they will care more about them.

“Whales in general are charismatic megafauna,” she says. “People appreciate and enjoy them, they are such a special species. So, I think there is motivation, and the public would be interested in seeing them safer.”