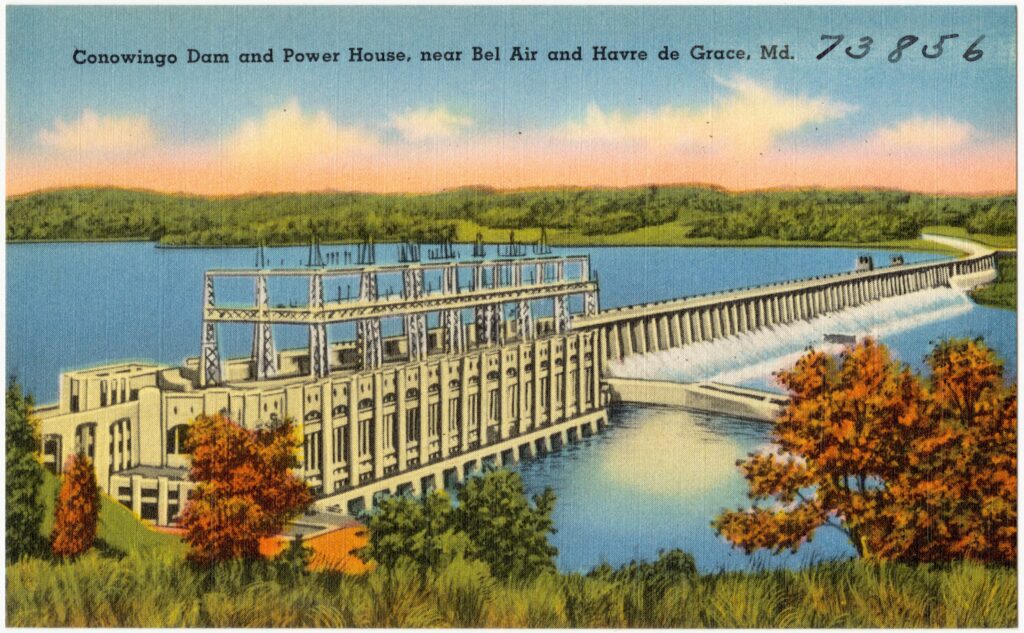

Illiustration: Wikipedia/Boston Public Library Tichnor Brothers collection

Story by John Page Williams

This week, four Eastern Shore counties dropped a key legal appeal, clearing the path for a $340 million settlement between the State of Maryland and Constellation Energy to go forward with an historic plan to reduce pollution impacts from Conowingo Dam. The settlement brings years of litigation and regulatory uncertainty closer to resolution.

The dam, a hydroelectric facility straddling the Susquehanna River just upstream of the river’s transition to the upper Chesapeake Bay, has been an environmental flashpoint for more than three decades. Built nearly a century ago, the dam once helped trap sediment and nutrients that would otherwise flow downstream. Over time, however, its fourteen-mile-long reservoir has filled with silt, losing much of its trapping capacity. As a result, large storm events dump pulses of sediment and nutrient pollution directly into the Bay, contributing to algal blooms, degraded habitat, and oxygen-depleted “dead” zones that jeopardize Bay restoration goals.

Efforts to balance renewable+ hydropower generation with environmental protection sparked a complex dance of lawsuits, administrative appeals, and regulatory negotiations. In 2018, the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) issued a Water Quality Certification under the Clean Water Act that would have forced stricter controls on pollution tied to the dam’s federal license. MDE waived that certification in 2019 as part of an early settlement, but environmental advocates argued that the deal failed to address the water quality impacts of the dam’s operations. A federal appeals court later invalidated the dam’s 50-year license in 2022, finding that the environmental conditions were insufficiently enforceable.

The disagreement centered not only on water quality protections but also on who should bear responsibility for the sediment and nutrient pollution from the states upstream in the Susquehanna’s huge watershed. Environmental groups—especially Waterkeepers Chesapeake and the Lower Susquehanna Riverkeeper Association—insisted that Constellation be held to enforceable standards, while utility interests argued that much of the pollution originated upstream and was not directly caused by dam operations.

After years of negotiation, a revised agreement came together in October 2025, when Maryland and Constellation announced a framework to fund multiple environmental projects and clear the way for relicensing. The settlement commits more than $340 million over the course of the dam’s 50-year federal license, including dedicated funding for pollution reduction, habitat restoration, trash and debris removal, aquatic life passage improvements, freshwater mussel restoration, invasive species management, and dredging studies to assess long-term sediment solutions.

The major funding allocations include $87.6 million for pollution reduction and resiliency initiatives (such as shoreline restoration, planting underwater grasses, and forest buffers) and $77.8 million for trash and debris removal. The new agreement allots more than $28 million to improve fish and eel passage around the structure, important because the dam has disrupted their historic migratory routes. Restoring eels to the upper river is crucial to restoring historic communities of water-filtering freshwater mussels.

Proponents of the deal, including Governor Wes Moore, have framed the agreement as a win-win for energy and the environment—allowing Conowingo’s hydroelectric power to continue supplying renewable energy for Maryland while ensuring stronger protections for the Susquehanna and Bay watersheds. Environmental advocates have also praised the deal as setting a precedent for how states can use Clean Water Act authority to secure enforceable environmental standards in federal licensing processes.

Still, some scientists and activists caution that the settlement does not fully resolve all ecological challenges. Dredging, for example, remains controversial. The agreement, does commit Constellation to pay for an $18.7 million dredging study, but the actual job would be massive. Most of us have difficulty visualize just how much sediment the largest river on the Atlantic coast of the United States has sent downstream to the dam over the past century. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is gearing up a two-year computer modeling assessment of dredging impacts on the reservoir and river downstream. Depending on the study’s results, MDE will plan how to use the dredging fund, into which Constellation must pay through 2050. If dredging proves to make sense, it will certainly demand substantially more public and federal investment. Legacy pollution in large river systems poses titanic challenges. At the same time, the upstream states will continue their not-inconsiderable work to reduce runoff pollution into the Susquehanna and its tributaries.

As projects begin to roll out and oversight mechanisms take shape, the Conowingo settlement represents a pivotal chapter in Chesapeake Bay restoration—a blend of regulatory authority, environmental determination, and pragmatic compromise. For a watershed long beset by contention, this week’s settlement advance may finally usher in a new era of cooperative stewardship.