by Jay Moore

Museums usually content themselves with changing your view of special slices of history. Howard Hoege wants the Mariners’ Museum to change your view of the world.

Hoege took over leadership of the museum in 2015, after an Army career that included West Point, Ranger School, and a stint investigating private security contractors in Afghanistan for the US Senate Armed Services Committee. He learned bow from stern aboard the charter fishing boat of his WWII Navy vet grandfather, and he sees the maritime experience as a common link for humanity.

“We’re all much more alike than we are different,” Hoege says. He believes that whether you live in Annapolis or Amsterdam, Nice or Newport News, we’re all part of one community. “It’s the water that links us together through shared experiences, whether at the city, state, national or global level.”

Visiting a museum, he says, is “not just about displaying artifacts, but having our visitors learn and feel something—an intellectual and emotional experience that is shared by generations, across cultures, and without barriers or judgment. We want to help each visitor find that personal link and leave feeling better connected to the larger community.”

The Mariners’ Museum is congressionally designated as America’s National Maritime Museum. It preserves the Western Hemisphere’s largest collection of maritime history with more than 78,000 volumes; 800,000 photographs, films, and negatives; and over one million pieces of archival material.

The Sailor Made exhibition demonstrates how mariners used leisure time to create objects and artworks that document life at sea, commemorate historic events or simply celebrate the extraordinary skill of the maker. Scrimshaw—carved or engraved by whalers from whale ivory or walrus tusks—is one of the most well-known, sailor-made arts.

Modern day road warriors accustomed to dashboard GPS and instant cellphone voice navigation can see the rudimentary tools that guided ancient sailors across the oceans. The Age of Exploration exhibit features 15th through 18th century quadrants, compasses, charts, cross-staffs, hourglasses, terrestrial and celestial globes and an astrolabe. The exhibit also includes coins, weapons, body armor and helmets used in times when diplomacy and bartering failed.

Explorers’ Theater is a permanent, high-definition theater, which “allows visitors to transcend the museum experience into the world of undersea exploration.” The theater presents short films on how maritime exploration has shaped mankind’s history, live feeds from exploration vessels around the globe, and 3-D films covering a wide range of maritime topics.

The museum sounds a clear “welcome aboard” to kids as soon as they enter. A Kids’ Activity Ship in the main lobby beckons them to take the helm, man the rail, and experience what life was like at sea.

Throughout the museum, kids can design an ironclad, lift cannonballs, interact with video kiosks to learn about small craft from around the world, and talk to a model ship builder carving balsawood.

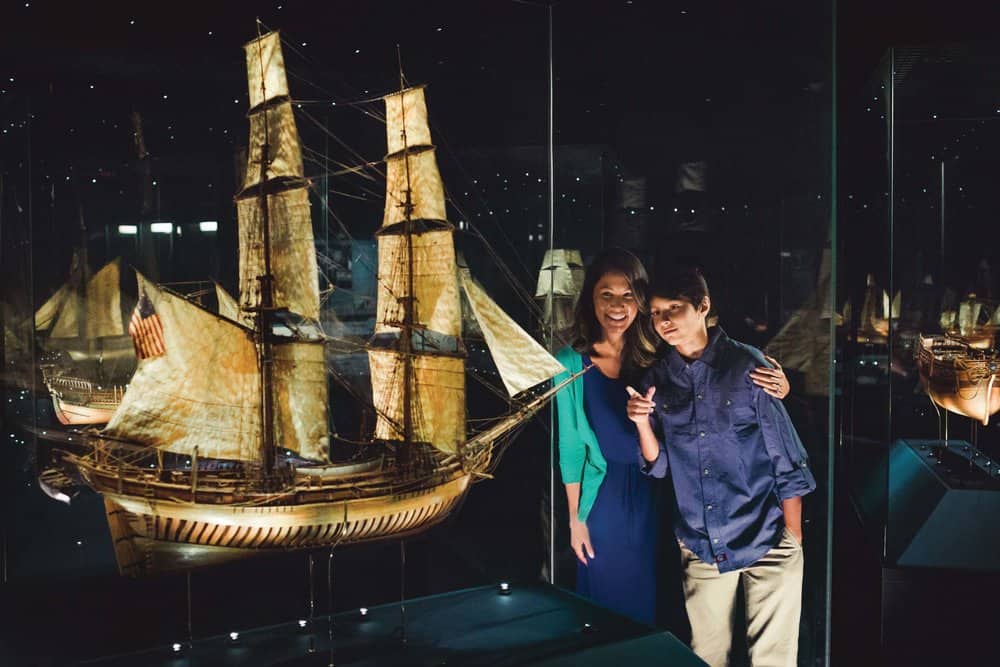

The Mariners’ Museum ship and boat experience is the next best thing to getting aboard a vessel. It’s up close and personal, with full size boats, scale models, and exquisite miniatures.

The 17,500 square foot International Small Craft Center presents the visitor with nearly 150 boats, displayed under themes including Maritime Environment, Culture, Shape, Materials, Conveyance, Sustenance, Competition and even Surfing.

Two exquisitely restored Chris-Craft runabouts highlight the exhibit. The 1923 Miss Belle Isle is one of the oldest known Chris-Craft boats in existence and originally sold for $2,950. She’s accompanied by the 1935 19-foot runabout Sue. The museum is also the repository of the complete Chris Craft archive, an important resource for historians and restorers.

A crudely built 7-foot aluminum kayak illustrates one of the most poignant stories told anywhere in the museum. In 1966, husband and wife Laureano Ricoy Iglesias and Consuelo Rivera Giz fitted the tiny craft with an old lawnmower engine and navigated 90 miles across the Straits of Florida over three days to the Florida Keys to escape communist Cuba.

“People come here because they want to feel and experience something, or they want to learn something,” Hoege said. Meanwhile, he has reorganized everything to achieve that end including marketing, development, and operations.

Hoege offered examples of how recent visitors told their family stories through museum exhibits:

A middle-aged couple and their granddaughter looked carefully at a large model of the SS Rotterdam, christened by Queen Juliana in 1958

as the pride of the Dutch merchant marine fleet. The woman turned to her grandchild and said proudly, “Your great aunt sailed on that ship.”

On one of his daily wanderings through the galleries, Hoege came across a 94-year-old man wearing the insignia of the Army 101st Airborne Division, the same unit Hoege served with in Afghanistan. As they talked, the man said he had “jumped into Normandy” in World War II and asked if the SS Strathnaver might be on display.

Pushing his walker closer to the large model of that ship, the man pointed to a starboard side porthole: “That’s the ship that took me to war, and that’s where I slept.”

“In the end, we always connect people to water, stir in them their connection to the water,” Hoege says. “If enough people identify with the water, maybe it can overcome some of the ways in which many folks feel they don’t identify with one another. Then maybe we can build a sense of community among people who don’t otherwise look or feel like each other.”

Jay Moore holds a 100-ton U.S. Coast Guard master’s license. He trains new boat owners on safety, boat handling and navigation when he is not serving as a ferry-boat or TowBoat U.S. captain.