As Chesapeake Bay scientists track concerning downward trends among species like striped bass, osprey chicks, and blue crabs, here’s one trend to be celebrated.

Bay scallops were wiped out by a disease that destroyed their baygrass habitat back in the 1930s, and remained extinct on Virginia’s Eastern Shore for more than 90 years.

A new report shows that, thanks to decades of baygrass restoration efforts, bay scallops are back in a big way—so big that the state may soon be able to consider allowing recreational fishing for scallops.

William & Mary’s Batten School & VIMS Eastern Shore Laboratory (ESL) released results of its most recent population survey, reporting an “unprecedented resurgence” of scallops multiplying exponentially in the restored eelgrass meadows of the Eastern Shore’s southern coastal bays.

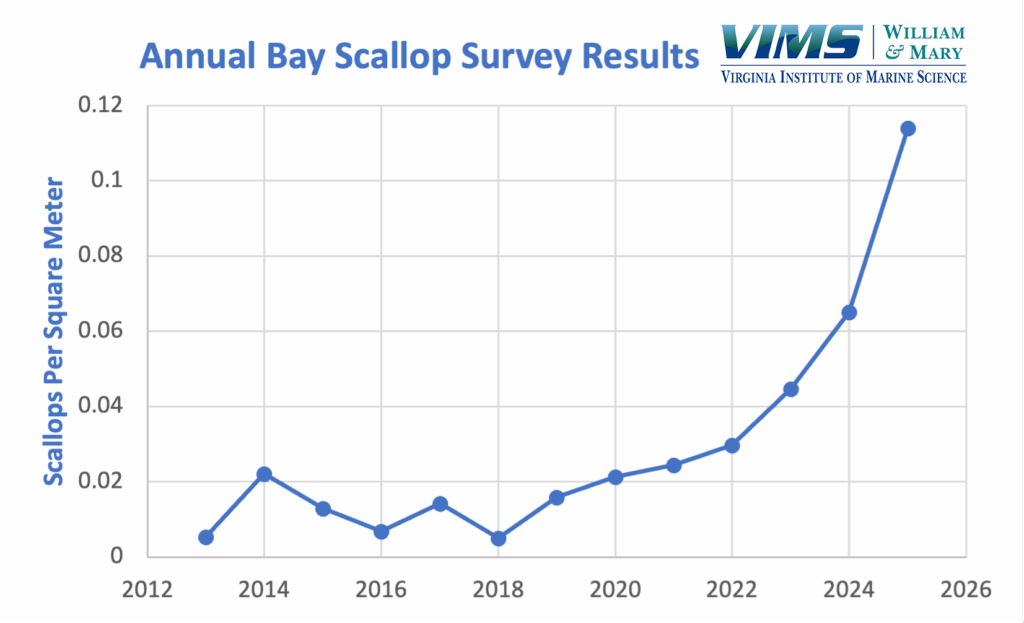

The VIMS ESL 2025 Bay Scallop Survey measured an average density of 0.114 scallops per square meter, and in many places, found multiple scallops within a single square meter. The researchers say that density would have been unimaginable just a few years ago. The population has now reached the density that Florida considers to be the minimum for a stable population. And based on current trends, VIMS scientists believe the Virginia population will double in the next year and a half.

Florida is one of three East Coast states where recreational scallop harvesting is allowed, and the way things are going, researchers say Virginia could be next.

“In New England, North Carolina and Florida, individuals with a fishing license can harvest scallops,” explains VIMS ESL Assistant Director Stacy Krueger-Hadfield. “The next step for us is to review management and regulatory frameworks being used for harvest elsewhere and provide advice to the Virginia Marine Resources Commission to establish rules for Virginia, so that we don’t decimate the population we just restored.” Currently, there is a moratorium on scallop fishing in the Commonwealth.

The restored population comes courtesy of an eelgrass restoration effort that began in 1997. Since a wasting disease decimated the scallop’s natural habitat in the 1930s, the mollusk had been absent from Virginia’s coastal bays. Then, Batten School & VIMS researchers launched a seed-based submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV) restoration project. Over the past three decades it has become the world’s largest and most successful seagrass project of its kind.

As eelgrass began to thrive, scientists saw their chance to bring back bay scallops. Their efforts yielded only small results in early years, but the population has grown exponentially. The difference is stark even since five years ago, says Chris Patrick, director of the SAV Restoration and Monitoring Program. “My team on the 2020 scallop survey only found a few scallops here and there, this year we found handfuls most spots we checked. It’s amazing and the grass habitat has also continued to expand and change. In addition to scallops we continue to see many other species responding positively to the restoration.”

“The growth suggests scallops are doing well enough to sustain the population on their own, not just relying on what VIMS ESL puts out each year from spawn,” Krueger-Hadfield says. It’s a promising development that the Virginia Marine Resources Commission will be watching closely.

“It’s incredibly fulfilling to see this progress,” said Darian Kelley, a nursery manager at VIMS ESL who works closely with regional shellfish farmers. “The combined success of the seagrass and scallop restoration efforts is creating a more resilient and productive coastal ecosystem while potentially adding a new product to our state’s aquaculture industry.”

Learn more about the scallops population study results on the Batten School & VIMS website.