All summer, the states of Maryland and Virginia found very promising water conditions in the Bay. Now it’s official—in 2023 the Bay’s “dead zone” was the smallest it’s ever been since monitoring began.

The Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and Old Dominion University collect water monitoring data from May to October. They’re looking at dissolved oxygen levels. Areas of hypoxia, which have extremely low oxygen in the water, are caused by pollution runoff and can be disastrous to marine life.

This year, DNR and Old Dominion monitoring found dissolved oxygen levels in the Chesapeake Bay mainstem were much better than average.

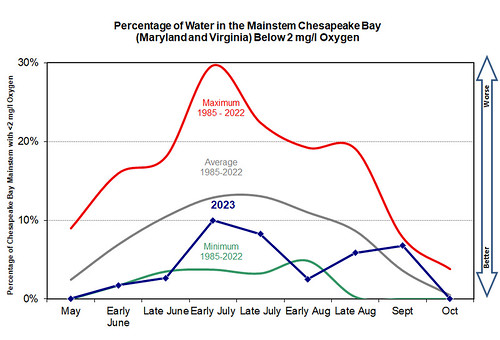

Hypoxic water volume, defined as waters with less than 2 milligrams per liter (mg/l) oxygen, were only half the size of the historical average. This year’s average of 0.52 cubic miles dipped to the lowest number seen since monitoring began 39 years ago.

Dissolved oxygen was better than average in May through August, with early August having the lowest volume of hypoxia ever measured during that time period.

“This year’s Chesapeake Bay dissolved oxygen conditions are the best on record, and it is encouraging news,” said Mark Trice, program chief of water quality informatics with Maryland DNR’s Resource Assessment Service.

Trice credits reducing nutrient pollution with shrinking the dead zone and improving fish, crab and oyster habitat. He does note, however, that watershed managers need to keep working at it. And the improvement didn’t come from human interventions alone: it’s also being attributed to lower than normal spring rainfall.

The banner year for dead zone reduction was not a total surprise. Researchers were able to predict a record low hypoxic zone based on freshwater flow into the Bay from January through May. Freshwater flow indicates how much nutrient runoff (specifically, nitrogen and phosphorous) may be entering the Bay.

This year’s freshwater inflows were near historic lows from January to June 2023, according to U.S. Geological Survey estimates.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) warns, however, that the hypoxia could come right back up in future years. In a statement, CBF Virginia Senior Scientist Joe Wood says, “As climate change also brings heavier and more frequent rainstorms that wash more pollution into our waterways, we can’t count on drier-than-average years to temper the Chesapeake Bay’s dead zone.”

Wood says that while wastewater treatment plant pollution has been effectively reduced, urban and suburban runoff is actually increasing.

NOAA noted that a hotter-than-average summer probably fueled some of the dead zone that did develop in the Bay. That’s because warmer air leads to warm waters, which hold less oxygen.

Maryland and Virginia combined results are presented for the mainstem Bay to be more comparable to the yearly seasonal forecast by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Chesapeake Bay Program, USGS, University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science and University of Michigan.

Bay hypoxia reporting will resume in May 2023.

-Meg Walburn Viviano