The annual juvenile striped bass survey results are in for Maryland and Virginia, and the news keeps getting worse. This time, it’s not just Maryland where the prized Chesapeake fish appears to be in trouble. Virginia’s count also came in significantly lower this year.

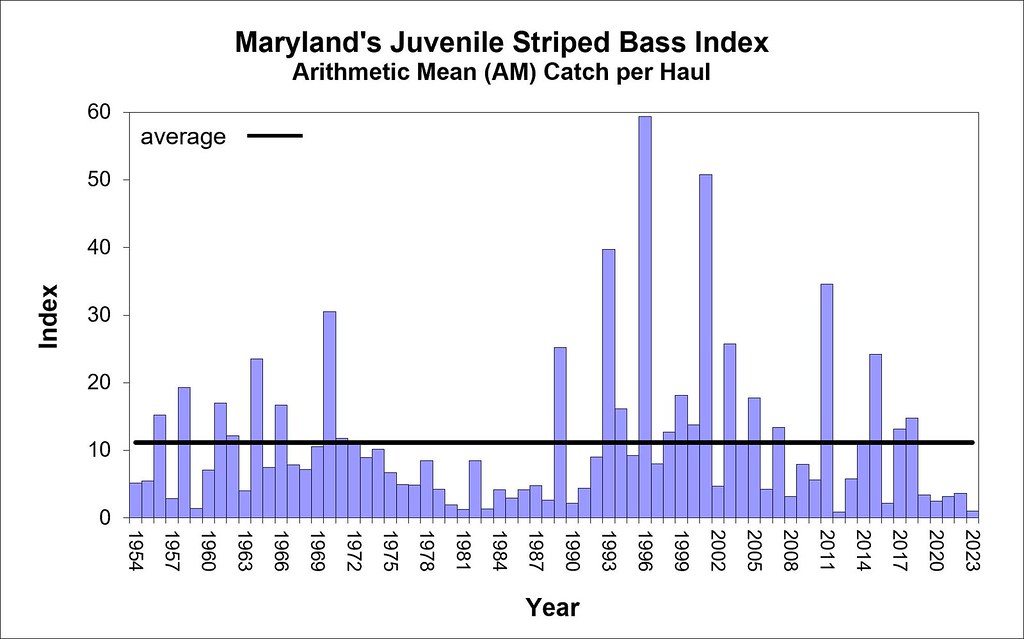

Maryland’s juvenile rockfish numbers had already been sitting well below average for four years. This year, they were the second-lowest they’ve been since 1957—the index sitting at 1.0 compared to a long-term average of 11.3. You can see the year-by-year numbers below:

Even Virginia, where the survey has been generally much more positive in recent years, saw poor recruitment in 2023. The Commonwealth’s rockfish index was significantly lower, with a mean value of 4.25 fish, well below the average of 7.77.

The results in both states show a recruitment failure, fishery experts say. Recruitment refers to the number of surviving fish that were spawned in the spring. The group of fish hatched this spring will grow to fishable sizes in three to four years, giving a snapshot of the predicted rockfish harvest a few years down the road. The Maryland survey is conducted by Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the Virginia survey by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS) on behalf of the Virginia Marine Resources Commission. This Chesapeake Bay Foundation video shows how the surveys work.

Maryland DNR points to ongoing climate conditions as a cause. “The warm, dry conditions in winter and spring during the past several years have not been conducive to the successful reproduction of fish that migrate to fresh water for spawning,” said DNR’s Fisheries and Boating Director Lynn Fegley.

The Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) also blames recreational rockfish harvest pressure along the Atlantic coast, estimated in 2022 to be “nearly double that of previous years”. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) instituted emergency action in May to decrease the maximum size limit for most striped bass fisheries to 31 inches.

CBF calls this year’s numbers “a disturbing trend”. Senior Regional Ecosystem Scientist Chris Moore says the poor recruitment shows that rebuilding the striped bass population is not guaranteed. “With five years of poor recruitment on the books, there will be fewer spawning adult fish left to help the population recover,” Moore says in a statement.

DNR now says it is “working with the ASMFC to support management actions we can take now to protect striped bass and improve spawning success.” According to Fegley, the agency is also considering additional state-specific actions to boost protections in Maryland.

In Virginia, VIMS calls 2023 “an off year” for juvenile rockfish, saying that recruitment can vary considerably from year to year. The last year with notably low recruitment was 2012, followed by 10 years of average or above-average recruitment. They say the strong years mitigate the effect of less productive years. Three continuous years of poor recruitment would trigger management actions to identify and address issues of spawning success.

DNR and VIMS look so closely at striped bass numbers because, not only are they a popular recreational sportfish and commercial fishery, they also serve as a top predator in the Chesapeake Bay ecosystem. Rockfish saw historic lows in the late 1970s, prompting total fishing bans in Delaware, Maryland and Virginia in the 1980s.

CBF’s Moore says there are several steps the Chesapeake Bay states should take.

“To increase survival, states must work with all fishery sectors to limit striped bass mortality through quota modifications, summer season closures, and addressing fisheries that target fish before they spawn. Anglers should also use careful catch and release techniques that keep released fish alive or target other species when available to reduce stress on striped bass populations.”

-Meg Walburn Viviano