Easton rediscovers the country’s oldest free black community.

A few blocks from Easton’s fancy restaurants and well-maintained historic buildings you’ll find a unique structure in the midst of a makeover.

The brown siding on the two-story home looks as though it has seen better days. A new wooden floor is visible surrounding the old fireplace through the space where the bottommost wooden sheathing should be. It may not look like much, but the house is part of The Hill, the earliest free African-American settlement in the United States, dating back to at least 1790 when the nation’s first census recorded 410 free African-Americans living there.

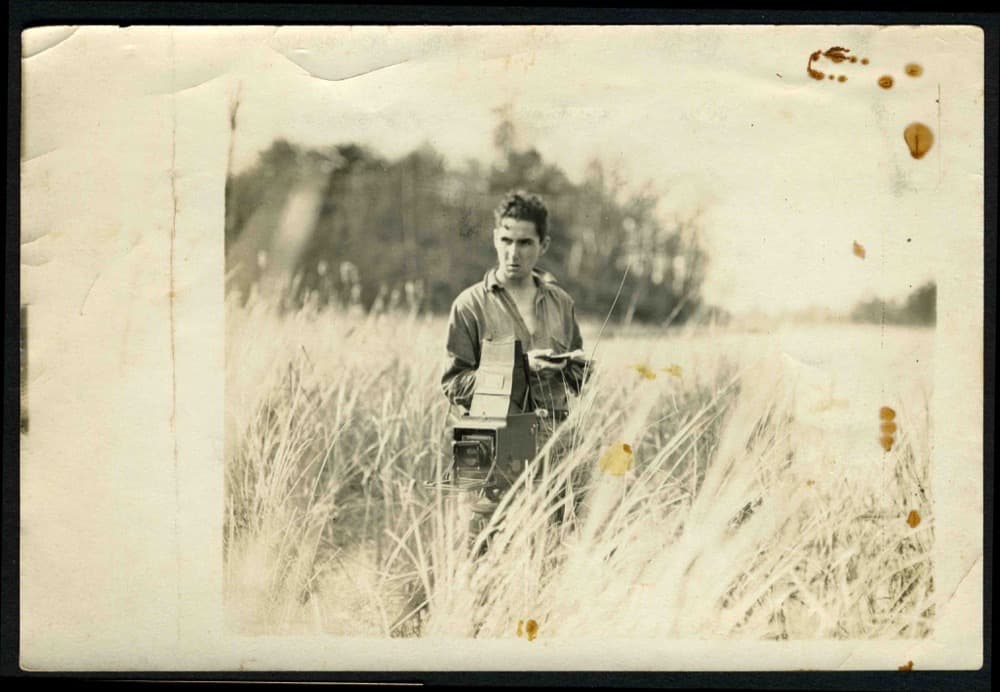

University of Maryland graduate student Tracy Harwood Jenkins explains as he walks through The Hill that the structure is known as the Buffalo Soldier House. John Green, a black soldier who served in the Civil War, began living in the home in 1879. After Green’s death, his nephew, a Buffalo Soldier named William Gardner, lived there.

Jenkins and other researchers from Morgan State University and the University of Maryland have been working on the home as part of their research into The Hill, a project launched seven years ago by Morgan State University architecure professor Dale Glenwood Green.

“This is a history that’s been buried, forgotten and undervalued,” Green told the Easton Star Democrat. “Everything is already here, it just takes an interest to uncover it all. All of this is led by curiosity and driven by the desire to learn about heritage, events and history.” Green leads group tours of The Hill by appointment through Talbot County’s tourism web site.

When Jenkins and other researchers first learned about the Gardner home, it was badly in need of repair and was slated for demolition.

“Sergeant William Gardner was a Buffalo Soldier who served out west, and his re-enlistment papers were found in the trunk of the house,” Jenkins says. “When we excavated, we found two military buttons that are from the late Civil War period that were probably from John Green’s uniform.”

Jenkins and the rest of the researchers have spent several summers digging for artifacts and taking clues from the things residents left behind to piece together what kinds of lives they must have lived. Animal bones can give hints about what these people ate. Shards of dishes can show whether a resident was looking for status symbols or living out of bare-boned necessity.

They hope that the work they are doing will help this historic segment of Easton get the same level of care and careful preservation as other historic communities.

“Shortly after our excavation in 2012, the mayor gave the building a stay of execution. Then, a couple of years later, the governor’s office designated, I think it was, half a million dollars for several houses on the Hill,” Jenkins says.

Just as important, researchers hope their work will help people consider two of the Eastern Shore’s most famous residents, abolitionists Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass, to learn more about the many who struggled to build lives for themselves in the face of inequality

and racism.

Jenkins says the Hill community has close ties to Douglass who wrote about being held captive in Easton after attempting to flee slavery. Douglass also dedicated the Hill’s two churches, which are as old as the community itself.

“The celebration of Douglass can sometimes border on tokenism,” Jenkins says. “So, our guiding question is, it seems like Douglass was very well aware of the free African-American communities that lived in Easton and throughout the country. How did that influence his concept of freedom and what it’s all about?”

He says that it’s important to remember that Douglass was not an anomaly, but rather, an outgrowth of a community that was looking to create better lives for themselves.

“The Hill is one of a number of free black communities that got established before the civil war. They were actually fairly well integrated into a network writing back and forth to each other, people moving around linked through the church by itinerant ministers, and there is a whole series of colored conventions that started in the 1830’s where free black people would get together and try to collaborate and figure how do we work together to improve our lots. They were setting up schools, they were working against slavery. Many of them had family and friends and relatives who were still enslaved, and so a lot of those communities have either moved because they have been displaced or something’s happened to them or they disappeared, but here on The Hill we have an opportunity to look at the whole trajectory from the 1780s up to the present with one neighborhood, many of the same families.”

University of Maryland Professor Mark Leone, who has also been working on this project, emphasizes this focus on community. “We have a free community of enterprising human beings supporting, later on, Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman,” he says. “My natural hypothesis or, our hypothesis, is that this is the community that helped to create those two American heroes. This is the village that brought them out and supported them. I don’t think you could have stations on the underground railroad without the communities that formed the stations. I don’t think you can have Frederick Douglass, as amazing as he is, standing alone without several communities behind him.”