Chesapeake oyster farms find their merroir

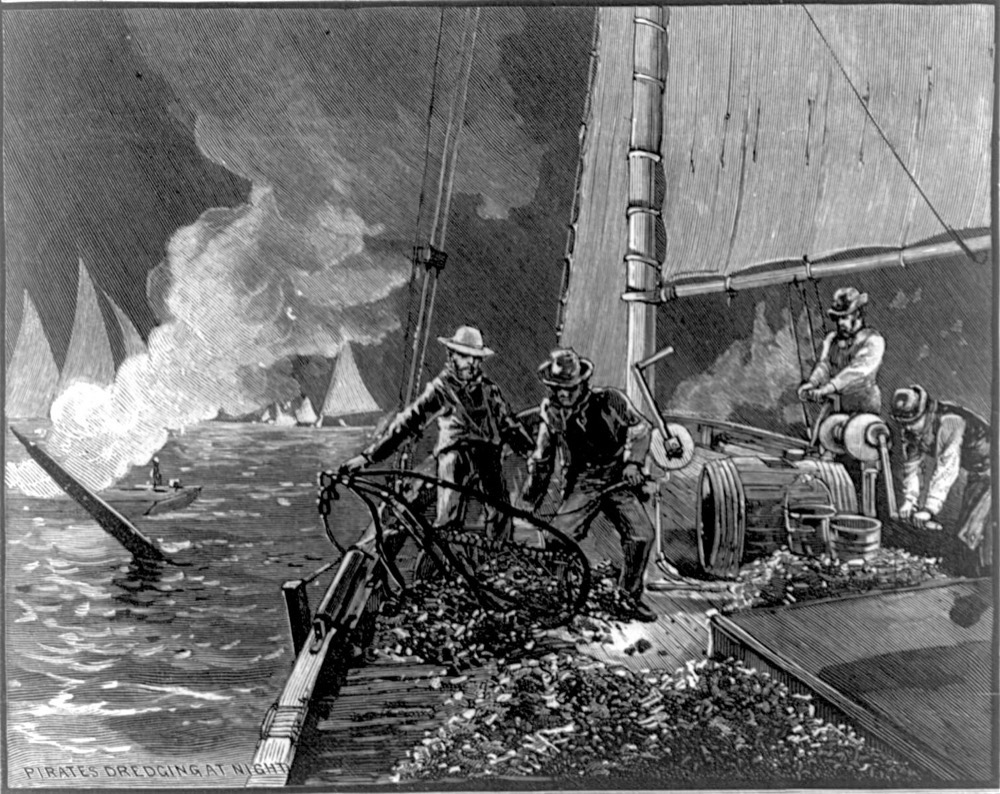

The temperature was hovering around freezing as the Commodore Maury set out into the James River near the Chesapeake Bay on December 19, 1907. The rain from earlier in the day had abated and it was clear enough that the men aboard the Maury could see the Jack Powhatan as she moved in the water. The moon might have been a benefit for both ships. The Powhatan needed the high tide the full moon provided to dredge oysters, and the Maury needed the light to see the Powhatan dredging. The Powhatan’s captain William B. Stant had been called “the most daring oyster pirate in Virginia,” and State Fisheries Chairman McDonald Lee, aboard the Maury, was eager to catch him in the illegal act.

Stant had apparently “boasted that he would not be arrested alive for unlawful dredging,” according to the Baltimore Sun, so when Lee heard Stant was going to be out on the water that night, he got his Oyster Navy together and the hunt was on. As the Maury approached the Powhatan, Stant cut the large metal rake and net that comprised the dredge from his boat and tried to get away. The Maury steamed ahead, spotlight on the target, and eventually caught and arrested Stant for illegal dredging. This wasn’t the first or last battle in the Oyster Wars.

In the 19th century, oystermen were pulling tens of millions of barrels of oysters out of the Bay each year. Piles of shucked shells around packing houses could stand taller than a building, workers canned tons of oysters for export, and the Chesapeake Bay was supplying nearly half of the oysters eaten around the world. While someone like Stant could pull up a lot of oysters in one go with his dredge, the metal rake also damaged the oyster reef.

This type of harvesting was not sustainable, and not healthy for the Bay. Between 1878 and 1879, U.S. Naval Officer Francis Winslow led a survey of oyster beds on the Tangier and Pocomoke sounds and stated plainly, “The number of oysters on the beds had been very much diminished since the commencement of the fishery, or during the last thirty years.” The huge piles of oyster shells were being used in limekilns or for fertilizer, which meant that spat (baby oysters) didn’t have the old oyster shells they needed to grow on. The continued heavy harvesting without replenishing the population would mean a collapse of the oyster industry.

In 1879, Virginia passed an anti-dredging law to try to protect the vast oyster reefs in the Bay and tributaries. But try as they might, the Oyster Navy and Oyster Police couldn’t seem to get the dredgers to stop. Stant only faced an hour in jail and had to relinquish his boat when he was found guilty of dredging.

The Maryland and Virginia governments realized there was a way to incentivize sustainable growth: Treat oystering not like hunting and gathering, but like farming. Have oystermen invest in not just this year’s harvest, but harvests for years to come. Maryland and Virginia began allowing people who were interested in growing oysters to lease barren waters of the Bay, sounds and rivers. Two hundred years later, oyster farms are still the best hope for sustainable growth—and delicious Bay bivalves.

On a clear, hot summer day on an unmarked one-lane road in Topping, Va., Ryan Croxton revs the engine of his truck, hauling a boat out of the water. Tanks for raising baby oysters and a machine that sorts the grown oysters sit on a dock that juts out over the creek. In between those two stages, the oysters grow in cages on the Rappahannock River—oysters that Rappahannock Oyster Company will serve across the world. It’s a tradition that goes back to 1899, when Ryan’s grandfather James Croxton took advantage of Virginia’s new oyster leases and began farming oysters.

“We adored our grandfather,” says Ryan, and so when his father and uncle asked if anyone wanted to take over the family’s 200-year-old leases, Ryan and his cousin Travis Croxton said yes, seeing it as a way to dig into and reconnect with their family history. But neither of them actually had any experience growing oysters. Ryan says they started by studying “dirt farmers,” and with that, they knew they had “to think about farming from a sustainability standpoint.”

Oyster reefs once stuck up above the waterline during low tide, but the way oysters had been overharvested was anything but sustainable. One problem was that without oyster shells, spat had nowhere to grow; oysters want to grow on other oysters, which is how they build reefs. Fewer oysters also meant less habitat for crabs and fish, and without the filtration oysters provide, dirtier water. Luckily, Ryan says, “the fishing in the Chesapeake had never gotten so bad that we’ve had to bring in a nonnative species.” We still eat Crassostrea virginica, as many generations have.

Although their grandfather was an oyster farmer, James would go to nearby areas to get wild spat and then raise those oysters on his plot. While this was better than dredging, Ryan points out, taking wild spat that would eventually end up on a plate still meant taking oysters out of the ecosystem and never replacing them, and never replacing the shells the spat needed to grow on. When Ryan and Travis started Rappahannock Oyster Company in 2001, they wanted to create a farming operation that was truly sustainable. This meant spawning and breeding oysters without depleting natural populations. Ryan explains you can do this by taking oysters inside and raising the water temperature to around 75 degrees Fahrenheit (or what it would be in the water during the normal spawning months), tricking the oysters into spawning and then capturing the larvae to grow. Today, a number of hatcheries and nurseries grow oyster seed and sell them to commercial farmers and individuals who want to grow their own baskets of oysters.

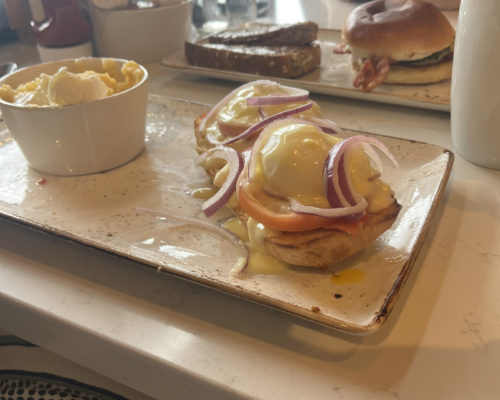

In the early years, Ryan and Travis bred oysters and cultivated them, then began selling them to restaurants. Then, says Ryan, chefs wanted to come see the farm and try the oysters. They set up a small place for tastings right next to where Ryan was pulling boats out of the water, with just raw oysters and a grill. “Then the business exploded,” says Ryan. We were gaining our taste for oysters back, and the Croxtons responded by building a restaurant in Topping, called Merroir, a portmanteau combining mer, the French word for sea, with the winemaker’s concept of terroir. Soon after came eponymous restaurants in Washington, D.C.; Richmond, Va.; Charleston, S.C.; and Los Angeles, where yes, they fly in oysters and the chef meets the plane on the tarmac.

When Patrick Hudson got the idea to start oyster farming in the late 2010s, he visited farms across the region, including Rappahannock Oyster. Like the Croxtons, he didn’t have experience with aquaculture, but the love of oysters drew him in. At the Chesapeake Bay Oyster Company in Virginia, he went out on boats and learned about the equipment needed for a farm, while at Island Creek Oysters in Massachusetts, seeing their farm, farm tours, and restaurants, he “saw the big picture and was inspired by it.”

Hudson began farming part-time in 2011, working as a paralegal to pay the bills. Even 10 years after the Croxtons began farming, Hudson says he saw how big the market was for local oysters, and so he got help from investors to buy the leases he had been farming on and expand his operation. Oyster farming is an investment, in both time and money. The tiniest, millimeter-sized oysters grow in large tubs, and every day you have to give them clean water and sort them by size. Once they are large enough, the farmers put them in cages in the water where they grow for two years before they are ready to be harvested. Those two years are hard: Croxton estimates that 50 percent of their oyster seed dies before maturity and Hudson says that when he first started farming, he was killing more oysters than he was growing. They’ve also taken the time to figure out the best water for their oysters’ merroir. All the oysters are the same species, but it’s where and how they grow that gives them distinct flavors.

Add to that time the money it costs to start a farm, including buying the oyster seed, the cages, and the complex sorting machines. “Purchasing seed is a huge cost—hundreds of thousands of dollars a year at our scale,” and yet that’s what makes what they do sustainable, says Hudson.

Another challenge, adds Hudson, is that “we don’t have control over our product overall, in the grand scheme of things.” They depend on the ecosystem to feed the oysters, and that ecosystem can easily be damaged by factors completely out of their control. “Sometimes you feel like a victim; between global warming and fertilizer runoff, you are completely helpless,” says Croxton. And yet, farms like these are helping the Chesapeake Bay and tributaries to become healthier. “Oysters on aquaculture leases are performing the same functions as wild oysters,” says Allison Colden, Maryland senior fisheries scientist with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation. “They contribute to filtration [and] nitrogen removal, and some of the aquaculture gear can also be serving as habitat in absence of natural oyster beds.” Which means some fish and crabs might find homes among oyster cages that float in the river or sit on the bottom of the Bay.

After the advent of oyster leases in the 1890s, oyster farming’s next breakthrough development didn’t come until the 1990s, with the triploid oyster. Although the biology behind these oysters is somewhat complicated, Hudson compares them to seedless watermelons. Triploids have been bred so that they can’t reproduce, which benefits oyster farmers in two ways. First, because the oysters are not spending energy trying to reproduce, they grow quickly and are generally larger than wild oysters. You can also harvest and eat them year-round, unlike wild oysters, which develop an off flavor during the summer spawning months (No more waiting for months with the letter “R”.) Around 90 percent of farmed oysters in the Bay are triploid oysters.

Although oyster farming seems complex, Croxton counters that it’s not high science. “The beauty of oysters has always been simplicity; you pick it up out of the water and eat it,” he says. That simplicity seems to be something that appeals to many oyster farmers and oyster restaurant proprietors.

After Hudson sold his first farmed oysters during Preakness in 2013, he met Nick Schauman, who had been shucking oysters at food festivals. They teamed up to open The Local Oyster at Mount Vernon Marketplace in Baltimore, which would highlight the Skinny Dipper, True Chesapeake’s signature oyster. Like the Croxtons, Hudson and Schauman found that the people wanted oysters, and felt good about eating fresh, local seafood. They soon opened a second Local Oyster in Arlington, Va., and then a flagship restaurant named True Chesapeake, located in the newly renovated Whitehall Mill in Baltimore. “Doing a big, fine-dining restaurant would be a capstone to the whole adventure and take everything to the next level,” says Hudson. But the adventure continues: They are currently working on another The Local Oyster restaurant in South Baltimore; a New Orleans-style oyster bar in Baltimore’s Remington neighborhood; and Hudson says he wants to double their oyster farm production.

The last two years have not been simple or easy for Rappahannock Oyster Company, True Chesapeake Oyster Company, or any other oyster farmers. Hudson estimates that 95 percent of oyster sales go to restaurants while only 5 percent go directly to consumers. When restaurants shut down in March 2020 because of the COVID pandemic, it meant that farms were unable to sell to restaurants, and they couldn’t even serve oysters at their own places. Since oysters only live for about three years, they have to be harvested. Colden, who works with oyster farmers through the Maryland Shellfish Growers Network, says farmers took a huge hit during COVID-related closures, and many pivoted to direct-to-customer sales through pop-ups and partnerships with grocery stores. True Chesapeake began selling pre-ordered oysters through MOM’s Organic Market and increased their sales through Whole Foods’ fish counter, which they’ll continue to do this winter. Colden adds that the Chesapeake Bay Foundation “hopes…that those people [who] have tried and enjoyed local Maryland and Virginia oysters” will continue to support their local oyster farmers.

Oyster cellars and saloons were once ubiquitous across the Chesapeake region, with shop owners shucking shells and carts selling door-to-door. The enthusiasm for oysters is growing again and hopefully the aquaculture industry can grow with it, bringing new restaurants and pop-ups, and new opportunities to eat oysters.