Two decades of collaborative research have paid off for Washington College students on Maryland’s upper Eastern Shore. They uncovered a key historic site that is now one of five Bay locations added to the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom. The Isaac Mason Escape Site stands out as a commemoration of American freedom-seekers and a testament to the work of these young historians.

Take a walk down Spring Avenue in downtown Chestertown and you’ll come across a sprawling maroon house with gable windows and a wraparound front porch. An old brick smokehouse stands on the grassy lot next door— the original location of the Mansfield home, where Isaac Mason was enslaved and eventually escaped on the Underground Railroad. Sometime later, the maroon house was picked up and moved next door. Its historic legacy has recently been revived, thanks to students from local Washington College.

Their project began 20 years ago. The history began almost 200 years earlier.

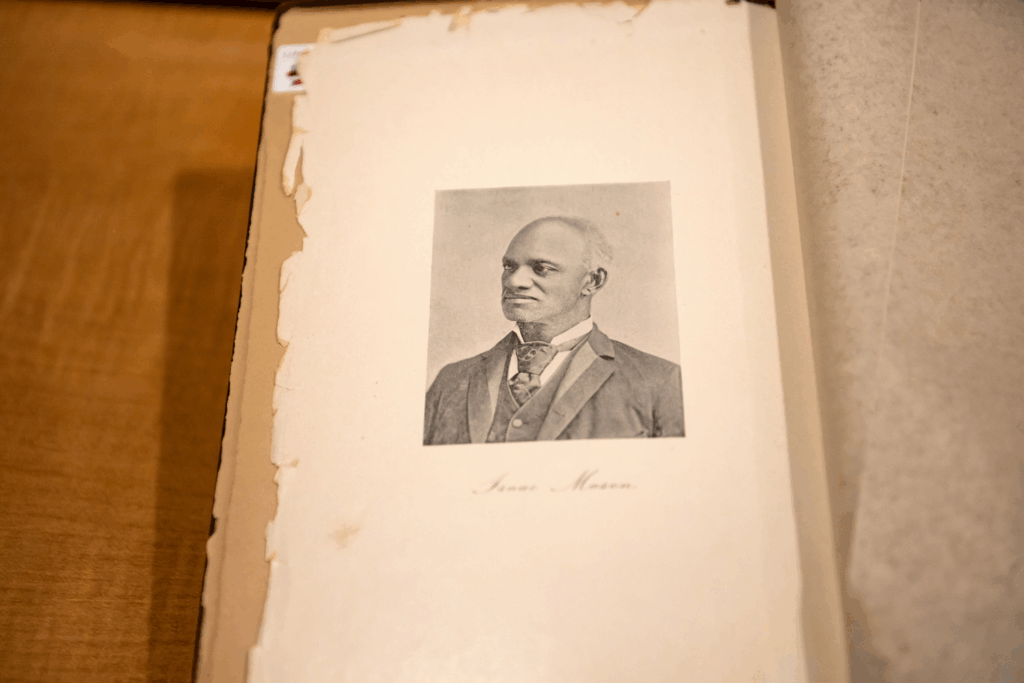

In 1846, an enslaved man named William Thompson fled the home of the Mansfield family in Chestertown. He changed his name to Isaac Mason upon arriving in Massachusetts and built a new life for himself as a free man. His 1893 memoir, Life of Isaac Mason As A Slave, gives a valuable autobiographical account of 19th-century slavery in the Mid-Atlantic region, but until recently the exact location of his enslavement and escape in Chestertown was unknown.

In 2007, Washington College student Albin Kowaleski identified 101 Spring Avenue as a possible address for the Mansfield home, connecting the name from Mason’s autobiography to past recorded owners of the house. Five years later, Kathy Thornton, a junior at the college, took the next step. While interning at the Maryland State Archives, she found a “Wanted” ad in a 19th-century newspaper with some familiar names: James Mansfield was in search of an escaped enslaved man named Bill Thompson— Mason’s birth name.

These documents paved the way for more rigorous research into Mason’s life by connecting the Mansfield family to his original name. “That was one of the big twists in the mystery that made it very challenging for us— these changing names,” said Adam Goodheart, director of the Washington College Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience, who led students on the project. The Underground Railroad was so risky that escapees would change their names to avoid punishment after they fled. “Kathy was able to trace Isaac Mason in the State Archives using his original name, William Thompson.”

But the researchers had another hurdle to overcome: according to oral history, the Mansfield house itself had been moved to the next lot over sometime in the late 19th century. But there was no documentation to confirm it. How could they prove that 101 Spring Avenue was the original house? “We had strong reason to believe it was,” said Goodheart, “but in order to get it onto the Network of Freedom, we also had to convince the federal government and a panel of professional historians.”

Just when they thought they’d hit a dead end, they had a breakthrough. In the fall of 2023, Kevin Hemstock, a local historian and former editor of Kent County News, found an archived newspaper article from 1893 announcing that the house was being moved. This was the missing piece they needed to finalize their report.

Washington College students and staff submitted a 45-page dossier to the National Parks Service for review. Goodheart assigned each of his students a different portion of the application: one compiled a recent history of the property, another researched land deeds, and another created a timeline of Mason’s escape. This past spring, the efforts of generations of students were rewarded: The Isaac Mason Escape Site is now officially on the Underground Railroad network.

“It’s just incredible to be part of something as an undergrad, and to realize that you can make those kinds of research contributions,” said Kathy Thornton (‘13), who was there for the early stages of discovery. “It’s really a testament to professors and mentors like Adam Goodheart, who are teaching young people how to ask questions, how to really dive deep into the sources and put together something that is meaningful.”

“Isaac Mason was an unsung hero of Maryland’s Eastern Shore,” said Emily Stiles (‘28), who worked on the final report. Although Mason was born in the same year as Harriet Tubman and wrote a memoir like Frederick Douglass, he is relatively unknown. This recent research milestone will help bring recognition to his historical contribution. His autobiography is a unique account of 19th-century slavery, especially valuable for its wealth of verifiable names and places.

Goodheart recalled reading the autobiography with students in the old Mansfield house. “Reading it aloud in the room where he was enslaved and under the roof where he was enslaved…” He paused with emotion. “That was just one of the most moving moments I can remember as a teacher.”

The building also happens to be the modern-day headquarters of the Kent Cultural Alliance (KCA), which has an artist residency program. A portrait of Isaac Mason hangs in the lobby, done by Jason Patterson, an artist and KCA board member. One Native American artist who moved in a week ago was inspired by Mason’s story to perform a smudging ceremony in the house— an indigenous spiritual ritual to purify a place. KCA seems an appropriate tenant in the building that was once home to a cultural influencer of his time. “He was a brilliant writer of nonfiction,” said Goodheart.

The research is not done: Goodheart and his students hope to pinpoint Mason’s exact birthplace in the nearby town of Galena. And it’s not all combing through dusty archives: a few months ago, they were “tromping around a cornfield,” he told us, looking for fragments of a 19th-century house.

There’s a lot more to discover, but Goodheart is hopeful. “Work remains to be done,” he said, “but that’s the historian’s favorite phrase. Work remains to be done. Always.”