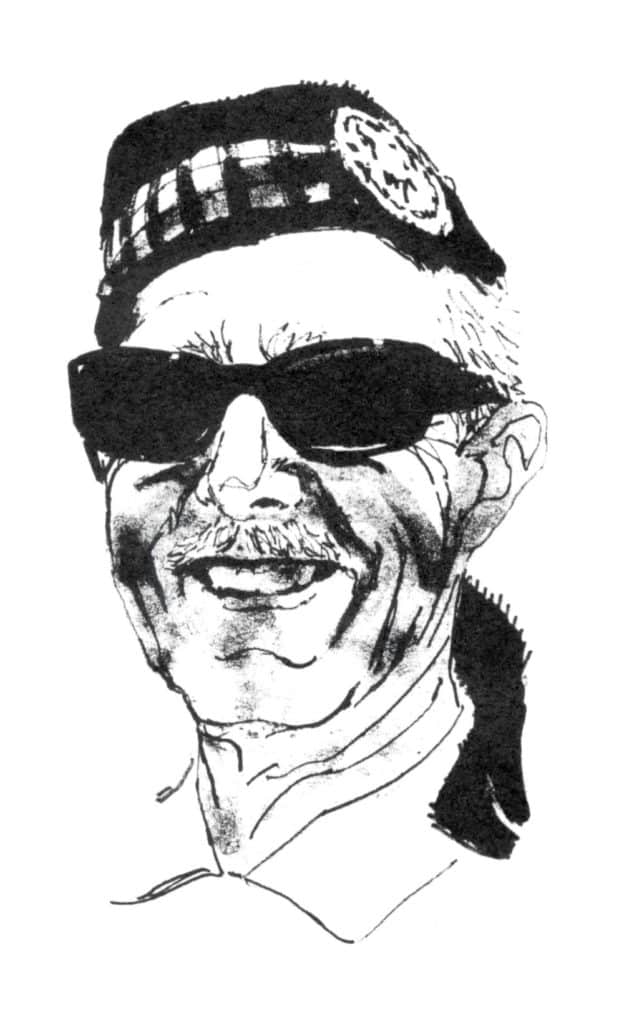

A successful sailboat designer is comprised of curiosity, art, skill with materials, education, craftsmanship and ego in varying percentages. Gordon K. “Sandy” Douglass, who created the Thistle, Highlander and Flying Scot one-design sailboats, possessed a bit less technical education and somewhat more self-confidence than others. He filled in everything else with focused determination and capped it all with salesmanship.

Douglass recognized that being born into a well-to-do family in a prosperous neighborhood launched him with a running start. His father was an upper-level manager for a New York company, and his passion was for canoes. By 1904, when Sandy was born, the canoe craze of the late 19th century was winding down, but racing these narrow craft under sail and paddle was still popular. Douglass grew up with the sport, and he excelled at it.

We don’t hear much now about the popularity of canoes in the 1880s and ‘90s, but it rivalled the simultaneous nationwide boom in bicycling, just as kayaks and SUPs have caught on in this century. Lightweight, simple, and easy to launch, store and maintain, the canoe became the first Everyman’s Boat. On any pleasant weekend, the lakes and rivers of New England were filled with couples and families on canoe outings.

Contemporary literature included adventure stories of canoeists who traversed remote areas and even crossed seas in the little craft. The 1866 publication of A Thousand Miles in the Rob Roy Canoe on Rivers and Lakes of Europe by J. MacGregor kick-started the craze. Almost half of Douglass’ autobiography, Sixty Years Behind the Mast, is devoted to his exploits in canoes. He brags of his successes, analyzes his failures, describes his innovations and draws a clear picture of life in a competitive upper-class family in the early 1900s. It’s worth reading just for the period atmosphere.

His life spanned two world wars, the booming 1920s and its crash, the Great Depression of the 1930s and the postwar Baby Boom economy. Family money insulated him from the worst of times. His father bought an island in Lake Ontario in 1936, which provided Douglass the freedom to pursue a tenuous portrait art career during the Depression. He supported himself working as a loftsman in a shipyard during the second World War, where he polished his design and construction skills.

But his life on the water started with canoes. Canoeing was not just about paddling, although he was quite successful in international competition with that. It’s also about sailing, and a slender canoe with a sail is a fast boat indeed.

Since the water of New York state’s lakes gets too hard for boating much of the year, he also embraced iceboating with enthusiasm. The man had a need for speed.

Simultaneously, Douglass developed skills in boatbuilding. In those days, lightweight canoes were constructed of thin layers of wood. A 19-foot sailing canoe might have thousands of tiny nails in it, each one driven with a hammer outside and a heavy drift inside to clinch the sharp ends over into the wood. This technique calls for meticulous workmanship and lots of time.

Much of Douglass’ later design inspiration was shaped by this early experience in such fast, unstable craft. He was thrilled by the speed and intense competition, but in time, realized that sailing canoes were a dead end. Like Chesapeake log canoes, they were so over-rigged and under-hulled that they would hardly stand upright in the water by themselves without a balancing crew. Heavy winds would knock them down and even moderate seas would bury them. That’s fine when you are young and athletic, but less appealing to older sailors, which corresponded to the time most people were established in jobs and homes and actually had a bit of leisure time.

Three forces drove the evolution of this hard-core canoe and iceboat builder and racer to the forefront of mid-century sailing dinghy design. One was studying Skene’s Elements of Yacht Design (1904) and Manfred Curry’s Aerodynamics of Sails and Yacht Racing (1928), which filled in his Dartmouth liberal arts education with some engineering knowledge. The second was competing against the legendary British master designer/builder, Uffa Fox, who developed the International 14—the precursor to every planing sailboat for the rest of the century. The final puzzle piece was U.S. Plywood’s invention of a process that could create complex shapes out of laminated wood veneers.

By the 1940s, Douglass had come to believe that a boat should be fast, sea-kindly and simple. It should also be fun to sail by an average couple, easy to build, and trailerable. And, it must be suitable for day sailing or racing competitively with other boats of its class. This formula, expressed as the 17-foot Thistle one-design in 1945, propelled him to the forefront of the small-boat world.

His timing was perfect. Servicemen were returning from the war and taking stable jobs in a humming economy as they settled down to raise families. These parents of the Baby Boom had some leisure time, discretionary income and an urge to own the latest stuff—cars, furniture, appliances and boats.

Along the way, Douglass invented lightweight sailing hardware made of stainless sheet steel instead of cast bronze. After the war, several new companies adapted his designs to create the familiar blocks and fairleads that sailboat racers use today.

Douglass and his partner, Ray McLeod, turned production of the Thistle into a thriving business in Ohio. He marketed the boat tirelessly, racing and establishing fleets around the country. By adapting the successful Lightning Class rules and keeping the boat strictly one-design he ensured that a sailor who bought a boat one year would not be outdated by next year’s model. Success in events like Yachting Magazine’s One-Of-A-Kind regatta in 1949 showed the Thistle to be fast, simple and fun. Douglass knew the top skippers of the time and capitalized on those relationships.

McLeod and Douglass disagreed on many things, from the design to production to marketing, and they eventually split shortly after introducing a new design in 1951—the powerful three-man, 20-foot Highlander. A friend of mine described a Highlander outing as similar to a ride on a sled down a steep hill—exhilarating but on the ragged edge of control.

McLeod continued to build the Thistle and Highlander while Douglass and his wife, Mary, moved on to plan his next project. Mary had considerable influence on his boats, his activities and his success. When her Thistle racing enthusiasm waned a bit, Douglass realized that it was time to move to different sort of boat.

The goal was to create a family boat that would combine trailerable size with comfortable seating for four adults, great stability, good speed and an easily handled sail plan. It had to be strong and require little maintenance. The result was his most successful design, the 19-foot Flying Scot, introduced in 1956, with a design much like the Highlander but easier to handle.

Fortuitously, the next leap in technology happened. Just as molded plywood made factory production of the Thistle possible, a new material revolutionized boat production—glass reinforced plastic (GRP)—fiberglass.

Building a fiberglass boat is much like building a molded plywood one, only more consistent and simplified by one step. In either method, the first step is a wooden prototype, which the designer sails, refines and de-bugs. Once the prototype is optimized, it becomes the male mold or “plug” for the female molds, which are made of fiberglass. In production, new hulls and other finished fiberglass parts are formed in molds, which are highly polished and waxed to keep the parts from sticking to the molds.

To build the wooden Thistle and Highlander, they used a machine that laid thin mahogany strips or veneers over a wooden form, which was smaller than the finished boat by the designed thickness of the completed hull. The strips are stapled in place. Typically, three to five layers were laid on at angles to each other with thermosetting resin between the layers. The hull was then vacuum-bagged to draw it all together and heated to set the resin. The result was a strong, waterproof piece of plywood shaped like a boat.

Hot-molded plywood boats can survive and remain competitive for a long time. Peter Hale, the Thistle Class historian, has an early 1946 boat by Douglass. It is beautiful in its natural mahogany finish, and she is still very ready to sail.

Douglass had the skills and was in the right place at the time. All he had to do was learn how to use fiberglass and resin to lay-up the hull in a mold. That is not a simple task, but he figured it out quickly and was cranking out the new boats within a year of making the prototype. Douglass’ boats were first produced in Ohio, but after the state decided to run the Interstate highway through his house, he relocated to Oakland, Maryland. In addition to Oakland’s attractiveness, reasonable housing and labor prices, it also

boasted the beckoning expanse of

Deep Creek Lake.

All the while, Douglass indulged in another passion: barbershop quartet singing. Over the years, he gained recognition within the Society for the Preservation and Encouragement of Barbershop Quartet Singing in America.

I never met the man who created the Flying Scot but my wife owns one, which we sail on a lake in Florida during the winter. It was his final design, and I consider it almost perfect as a family boat for day-sailing and racing. Its few flaws, a result of Douglass’ stubbornness, are not fatal, only anachronistic.

The Flying Scot is exceptionally stable, a result of wide beam and unique underwater shape. A full-sized man can step onto the foredeck from the dock and the boat stays nearly level—remarkable for a 19-foot center-boarder. This stability also means it’s easy to move about underway and do all the things you need to do when sailing a small boat. As with every boat Douglass built, it is strong. Structural problems are rare even after decades of racing.

An average couple can sail and race a Flying Scot without great athleticism. Douglass hated hiking straps and, following his lead, the class forbids them. The annual Wife-Husband Regatta tells you what you need to know about the prevalence of couples in the class. The seats are exceptionally comfortable for day-sailing and the motion and simple layout of the boat instill confidence.

The Scot rig is a simple sloop with only two serious flaws: a medieval reel wire halyard winch that breaks handles regularly and a long-discredited roller furling boom system. These remain out of sheer determination to not change anything.

The boat is fast enough, although not a hot performer by today’s standards. Few would consider it as pretty as the Thistle. Peter Hale told me about Douglass proudly bringing the first Flying Scot to the Rochester Canoe Club to promote it, but Hale literally sailed circles around it with his Thistle on the race course.

Douglass’ boats have never been the least expensive on the market, as there’s no skimping on quantity or quality of materials. A new Flying Scot costs about $25K. Older models hold their value well, so an owner ultimately gets more back after years of trouble-free sailing than someone who buys a cheap boat that weakens and depreciates rapidly.

Thistles are still racing. A new one costs about the same as a Flying Scot. There have been several builders over the years but all stick closely to the one-design hull and rig conformation, keeping the older boats race-worthy. Builders switched to fiberglass some years ago, but wooden boats remain competitive on the race course.

Besides, old wooden Thistles are flat-out gorgeous, with shining varnish over mahogany, oh my.

The Highlander class is still going, with newer boats being built of fiberglass by Allen Boat Company in Buffalo NY, but the class never grew as large as either the Thistle or the Flying Scot.

Harry Carpenter, who bought Flying Scot Inc. from second owner Eric Ammann in 1991, started working for the company in 1978. He knew Douglass well, so he shared a number of insights with me in a recent interview. A longtime competitor in the class, Carpenter had him as a racing crew once and found that Douglass liked to cover, not break away. “He was very calm when racing, never raised his voice,” he said.

“Douglass often said there were two sides to every argument—his side and the wrong side. He was very blunt. Very polarizing. You either loved him or hated him. He was very opinionated, and once he formed an opinion, he didn’t change. That held in other areas, such as politics, as well as in boat building.”

“Sandy was a perfectionist. Once, he watched an employee who was varnishing and said, ‘There’s a bit of a dry spot here.’ The worker said, ‘Here, you do it,’ and dumped the can into the boat.”

With all that, the work force at the factory has been remarkably stable. The current shop foreman has been there 35 years. “It took the right personality to get along with Sandy,” Carpenter noted.

Douglass retired from national racing and sailed only locally after selling the company. He travelled, going to Europe at least once a year, but seemed to have no desire to compete there.

Douglass’s son, Alan, had no interest in sailing or in the company but Douglass made him work summers in the factory during his school years. In rebellion, Alan grew long hair, a hazard in factory work. Then, one day he simply broke all the drill bits and left. But the family history of woodworking and music endured, and Alan later became a successful maker of pedal steel guitars.

After a family reconciliation, Sandy and Mary moved to New Mexico to be close to Alan, where they lived out their lives.