by Gary Reich

It takes a unique and maybe slightly crazy person to look at what is essentially a pile of decaying, shrink-wrapped lumber on eBay and see the potential for a fully restored offshore fishing boat. For the challenge of saving two dumpster-bound stacks you’d need a dynamic duo afflicted with the precise mix of dedication and, well, cheerful craziness. Luckily for a couple of long-neglected Rybovich sportfish yachts, Reid Bandy and Mark Hall are the two individuals who have the right stuff.

In taking on the ownership and salvation of a pair of 60-year-old boats, the two have invested nights, weekends and much of any leftover spare time orchestrating a complete side-by-side rebuild of the tortured old hulls using a blend of new and old boatbuilding techniques and materials. It’s happening in a small boat shop at Casa Rio Marina in Mayo, Md., where the boats have been transformed from the stuff of nightmares into stunning displays of persistent craftsmanship. The projects fulfill the lifelong dreams they share of owning Rybovich boats, perhaps the most storied and legendary name in sportfishing yachts.

Humble Beginnings

Despite Bandy and Hall respectively managing day jobs running auto restoration and home contracting businesses, the two craftsmen have deep roots in boats and boatbuilding. Hall attended boatbuilding school in Maine in the ’70s and spent time in the United Kingdom for a boatbuilding apprenticeship before returning home to Annapolis. He worked at Topaz Boats in Southern Maryland for a while but ultimately found himself tinkering with houses more than boats. He’s been in the home business for 30 years, specializing in historic restoration and general contracting.

Bandy sailed one-designs with his father as a kid in Chesapeake Bay Yacht Racing Association-sanctioned regattas but eventually started messing around in fishing boats around the time he was a teenager painting cars in his driveway for extra money. “I never was an out-of-the-box boat kind of guy,” Bandy says. “I much preferred buying junkers and fixing them up the way I wanted.” By the time his Elite Auto Body business was successful Bandy was thinking about designing and building his own boats. Today, as if the Rybovich project weren’t enough, Bandy is building his seventh custom boat, a 24-foot ultralight carbon fiber center-console conceived to run 50 knots with a 90-horsepower two-stroke Yamaha outboard.

Online Commerce

The Rybovich end of this story begins one evening almost two years ago when Bandy was recovering from surgery. “I had messed up my shoulders pretty bad and had to have surgery, so I didn’t have many better things to do than sit on the couch,” Bandy says. “I ended up spending a lot of time on eBay looking for car parts for my auto restoration projects. Eventually I ended up wandering across an old 36-foot Rybovich hull. Then I found another 36-footer a little farther down the page. That’s rare.” Bandy initially ignored the two finds. “I didn’t pay them much attention; they were in pretty rough shape,” he says.

Bandy and Hall had been sharing magazine cover photos and stories about Rybovich sportfish yachts for years and had frequently toyed around with the idea of fixing one up for themselves. “Mark had a 1960 Pacemaker 30 and I’ve had all sorts of sportfish boats, including a 1990 Jarrett Bay 53. To us, a Rybovich is the epitome of a sportfish yacht. Rybovich was the first in the game. Carolina sportfish boats came after Rybovich had built at least four or five of their own boats,” Bandy says. “They’re works of art; the curves are perfect. When I saw those two boats were still on eBay a few days later, I called Mark. Two days later we were flying down to Palm Beach to look at them.”

Package Deal

The two boats were under the care of longtime Rybovich employee Bob Bingham, who had acquired a handful of old Rybovich hulls in various states of disrepair. Inside each shrink-wrapped hull Bingham placed essential boat hardware, building lumber and whatever else he could gather for eventual restorations. “We looked at the boats first on Saturday. Both were in pretty bad shape but one had had a decent amount of work done to her bottom and topsides,” Bandy says. “The other was in really bad shape; I was surprised someone hadn’t simply driven a Bobcat through her and pitched what remained into a dumpster. Mark and I slept on it for a night and went back the next day to try and strike a deal.”

Bingham had a figure of $10,000 in mind for both of the boats. Bandy and Hall countered with $5,000. By the time all the haggling was over Bingham settled for $9,000 for the pair. “Despite how fast everything went it wasn’t an easy decision,” Bandy says. “We had to ask ourselves whether these boats were worthy of our money, worthy of the time and expense of fixing them up, and if they would be boats we’d be proud of when we were done. Mark’s boat was in better shape, so he took that one, and I took what I called the ball of puss. Mark had boatbuilding experience but I knew I’d ultimately feel better about having the more challenging boat.” Within a couple of weeks, the two hulls were northbound on Interstate 95, strapped to two flatbed trucks.

Storied Pasts

Though both boats have good back stories, Bandy’s is the more colorful. Built in 1955, Bandy’s boat, named Timid Tuna, was the second Rybovich built for Tony Accardo, a mob gangster and hitman dubbed the “Big Tuna” by the Chicago press while working for Al Capone. “Accardo also owned hull number two,” Bandy says, “Accardo had seen hull number one, Miss Chevy II, win the Cat Cay Tournament in Cuba and he wanted one just like it, but a little longer. So, he had Clari Jo built in 1949. She was a 37-footer. Six years later he had my boat built, hull number 18, and named her Timid Tuna.”

The story goes that the FBI was keeping an eye on Accardo, so his people were telling him to keep a low profile. Accardo’s response was to have the topsides painted bright pink. The color and the name were pretty much his idea of giving the FBI the finger.”

Hall’s boat, Butterball, is hull number 12, built in 1954 as a surprise gift for Frank Lasier from his wife. The name affectionately refers to Lasier’s wife, who was apparently, ahem, big-boned, according Rybovich lore. Hall’s boat arrived at Casa Rio Marina in rough shape but better than Bandy’s Timid Tuna, which was not much more than a skeleton.

Methods and Materials

Bandy and Hall knew that they’d be using a variety of techniques to rebuild the hulls and that each boat would require its own battle plan. For Bandy that meant a Sawzall reciprocating saw would become his new best friend. “I started by cutting out and removing frames. I used the old frames to cut a template for new ones out of construction lumber,” Bandy says. “But I eventually realized that I should just cut the new frames right off the pattern for the old ones as I removed them, so I began cutting new frames right out of clear Douglas fir. When I was done maybe two or three original frames remained.” Once he stabilized Timid Tuna’s framework he and Hall set about flipping the two boats over and rebuilding the hulls.

Butterball’s bottom had been partially cold-molded and her topside planking was in decent shape. “The work we had to do to my hull was fairly insignificant compare to Reid’s,” Hall says. “But we both wanted to convert the boats from twin to single-engine power. That meant we needed to undo some of the work on my boat before we could wrap up her bottom and topsides.” Bandy engineered new running gear tunnels for the boats using CAD software to accommodate the single-engine setups. “I wanted to get some buoyancy out of the sterns of these boats and have a low shaft angle; this gives the boats a bow-high orientation,” Bandy says. “So that meant we had to modify a lot of interior components and bottom surfaces before we could seal everything up.”

Once the tunnels were in and the new okoume plywood cold-molded bottoms finished, the pair set about filling and fairing the old topside planking with high-density filler. “We just walked around the boats with a bucket of filler and when we saw a seam or hole we filled it up,” Bandy says. “You just sort of keep walking around the boat until all the imperfections are gone.” Next they sanded the hulls fair and wrapped them in three layers of 17-ounce biaxial fiberglass cloth saturated in epoxy resin. Once cured, they sanded and coated the hulls with high-build primer. “You go through a lot of sandpaper,” Bandy says. “We sanded and sanded until the hulls and topsides were in good shape and then painted them. Mark’s boat is yellow; mine is pink, just like the original. I get a hard time from a lot of folks about that hull color, but I wanted to stay true to the original because of the mob-connected history of this boat.”

Bandy and Hall then sanded out the new frames and the interior hull sides and sealed them with coats of Marpro laminating epoxy resin.

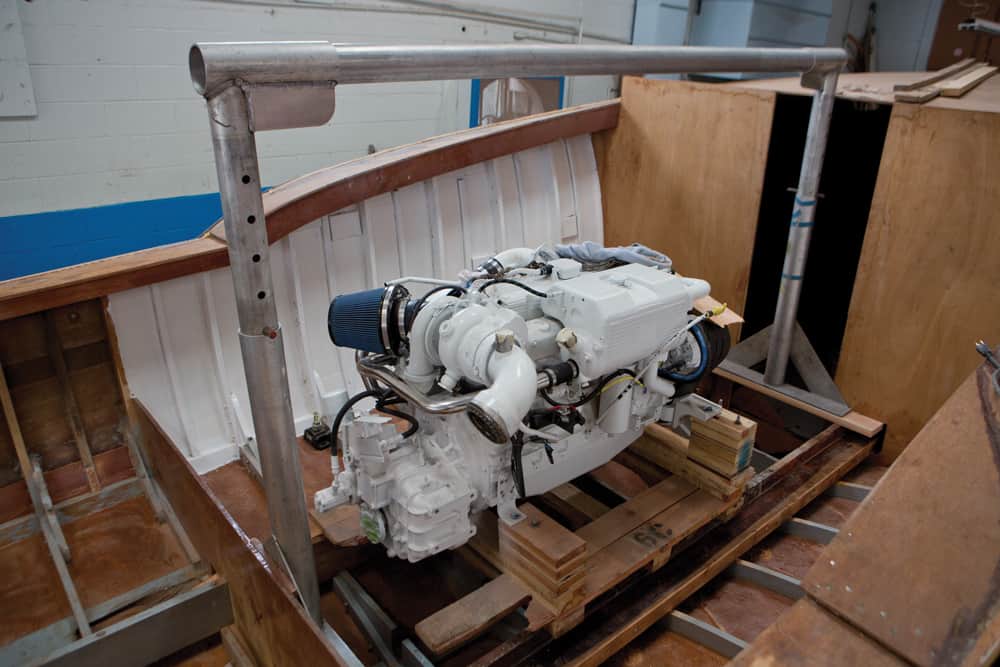

The engines were the next task at hand. They went in search of 600-horsepower Cummins diesels. Hall went with a reconditioned model that had been stripped down to its essential components and reassembled with new or remanufactured parts. Bandy decided on a used model with about 1,000 hours on the clock. “Getting the engines in was pretty easy,” Bandy says, “I had mine repainted and got a new transmission for it and had custom engine mounts ready to go. We’re hoping both boats will run 30 knots in the corner and cruise at 25 knots.”

Modern Materials

The next phase of rebuilding is where both projects take high-tech turns. Instead of reconstructing the boats’ decks and cabinhouses from plywood and timber, Bandy took a page out of his own boatbuilding playbook by using Corecell closed-cell panels, more commonly found in high-tech sailboats. The high-density PVC foam panels are covered in fiberglass cloth and epoxy to form immensely strong but lightweight sandwich-like structures. “I knew I wanted to use Corecell throughout my boat,” Bandy says. “I’ve built plenty of boats with it and I knew it would work great for these old Rybovich boats. It’s much lighter and stronger than wood and ultimately more durable.”

They built mockups of the old cabin houses and put them into a CAD program to guide them in building jigs for the composite structure, essentially male molds of the cabin houses. The Corecell was then bent and fastened to the jig stations, glued at the seams with Gorilla Glue, then sheathed in fiberglass and epoxy. Last, the jig was removed and the backside of the Corecell sheathed in fiberglass and epoxy. “That cabinhouse weighs about half of what a wood house would weigh, and it’s stronger than frames and plywood would ever be,” Bandy says.

Bandy’s interior is sticking with Corecell and fiberglass construction for the cabinhouse, decks, cockpit and interior soles, bulkheads, interior furniture and other interior fixtures, producing modern-looking curves and radiuses, resulting in a modern look. Bandy also raised the cabin height by seven inches to suit his six-foot, seven-inch frame.

A look inside Hall’s boat reveals a higher utilization of wood. “I’m a wood guy,” Hall says, “I wanted a warm feel below, so a lot of the bulkheads and other interior aspects I did in wood. Maybe it means my boat ends up being a thousand pounds or so heavier than Reid’s boat, but I can live with that. The cabinhouse and a number of deck elements utilize Corcell just like Reid’s boat, though.” Hall has created a beautiful wraparound wood bulkhead in his boat’s forward cabin, as well as a gorgeous teak-trimmed offset berth in the bow.

To keep his boat low maintenance, Bandy is playing around with unique technology. The mahogany transom isn’t mahogany. Bandy had famed maritime and fashion photographer John Bildahl take super high-resolution images of select pieces of mahogany and transferred the pattern to sheets of the same wrap material used on show trucks and cars. It’s nearly impossible to tell that it’s not real from outside of a foot away. This is the transom accent. Bandy is also using the system to create faux-teak toe rails for the boat. In the cockpit, Bandy has a sheet of teak-look foam decking laid out. “It’s awfully close to the real thing these days,” Bandy says. “I’ll use it in the cockpit and maybe the bridge deck.” The goal is less maintenance work and more time spent enjoying the boat. “I’ve had boats with lots of wood,” Bandy says. “I’m sort of done with that mess.”

Hall and Bandy expect it be another year before they will splash their boats. “I’m hoping for next spring,” Hall says. “Me, too,” replies Bandy. The two plan to keep the boats on the Bay for a year or two before they take them offshore to pursue billfish and tuna. So, if you happen to find yourself driving past Casa Rio Marina in the evening and you see the midnight oil burning, chances are that Hall and Bandy are inside hard at work on bringing Timid Tuna and Butterball back to life.